How much is your Face worth?

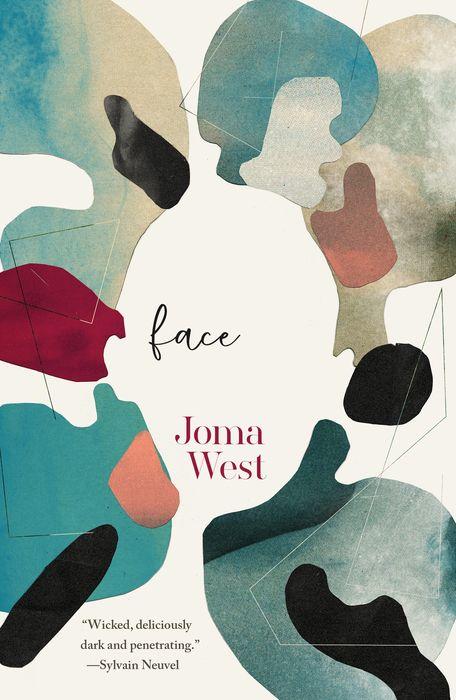

We’re thrilled to share an excerpt from Face by Joma West, a sci-fi domestic drama that reimagines race and class in a genetically engineered society fed by performative fame. Face will be available August 2nd from Tordotcom Publishing.

How much is your Face worth?

Schuyler and Madeleine Burroughs have the perfect Face—rich and powerful enough to assure their dominance in society.

But in Schuyler and Maddie’s household, cracks are beginning to appear. Schuyler is bored and taking risks. Maddie is becoming brittle, her happiness ever more fleeting. And their menial is fighting the most bizarre compulsions.

Naomi

Menial 63700578

Naomi was reading the assigned textbook from Morton’s psych class. Psychology: The Science of Mind and Behaviour, 98th edition. It was interesting, but it didn’t tell her much more than she already knew. It just gave fancier names to everything. She was meant to be preparing a project; a study in Individual Differences. She had to pick a case-study and find a real-life equivalent. The project felt dull and uninspired. She could already see the results, and everyone’s project would be the same. It would be easier just to make it all up and put together the presentation ahead of time.

As she came out of the In, she heard the murmur of speech. Schuyler was talking to Reyna in the hallway outside. It was dinnertime. An alert flashed up at the bottom right-hand corner of Naomi’s vision:

Madeleine: Dinner

Buy the Book

Face

Naomi shut down her AR function. She sat still for a moment, gathered herself, pasted a sarcastic smile on her face and went downstairs.

‘Where’s Naomi?’ she heard Schuyler say.

‘I called her a minute ago,’ Madeleine told him.

‘Present and correct,’ Naomi announced herself.

‘Sit down,’ Schuyler said.

As they sat at the table the menial came in pushing a trolley. It moved with care, placing plates before them. Naomi watched it work. Odd creature.

‘What are you having today?’ Schuyler asked everyone.

‘Isn’t it obvious?’ Naomi asked back. The words came out mechanically, their pitch was automatic.

‘Well, if it isn’t the teenage cliché,’ Reyna muttered and, despite herself, Naomi found that the words stung. It surprised her. She had heard them before and it usually never mattered. She did her best with what she had.

‘Oh sorry. Do I disappoint you, Miss Original?’ she asked Reyna.

‘Disappointment requires prior expectations and I’ve never expected anything from you,’ Reyna said, smiling sweetly.

‘Now girls, I expect a higher form of face from you. You’re both capable of more than this,’ Madeleine said.

‘Ah, so you’re the disappointed one,’ Naomi said, grinning at their mother. It was a relief to turn her face on Madeleine, always the easiest one to wrangle within the ‘family’.

Madeleine didn’t dignify the jab with a response—Naomi didn’t expect her to—and they all began to pick at their food in silence. As soon as the first course was over, the menial emerged from the kitchen. Naomi watched it as it walked around the table. What was it thinking as it sat alone and watched this ‘family’ eat together? Its face was gormless; slack jawed, like it was doped. Naomi wondered if that was the default menial ‘face’. She hadn’t really looked at them before. It was proper to treat them as invisible. And then the idea occurred, as naturally as an exhalation. Menials. They could be her project.

‘Tonia and Eduardo have decided to choose a baby,’ Schuyler said, breaking through her thoughts.

‘I know, I think it’s wonderful!’ Madeleine said, her voice setting Naomi’s teeth on edge. The gushing, passive-aggressive positivity was nauseating. To all of them. Naomi grunted.

‘You think it’s a bad idea?’ Schuyler asked her.

‘It’s a minefield,’ Naomi told him. ‘And they’re green.’

‘They’re also static right now,’ Reyna said. ‘Having a child is the only way for them to move up the social hierarchy.’

‘If they get it right,’ Naomi said. ‘It’s a gamble and they could slide either way.’

‘If we give them a helping hand we can make sure they slide up,’ Schuyler said.

‘And what do we get in return? Favours shouldn’t be freely given. Honestly, I don’t really understand why you bothered making “friends” with them in the first place. They don’t add to your cachet at all.’

Schuyler smiled at her. Naomi didn’t like it. It was one of his inscrutable smiles and she had learned a long time ago that inscrutability was belittling.

‘Well, that’s the best thing you’ve said in ages, Naomi,’ Madeleine said, and if Naomi could have winced with impunity she would have.

‘Just because you can’t see the benefit outright, doesn’t mean it isn’t there,’ said Reyna. ‘You’re only looking three steps ahead, little sister. Try looking ten.’

Those words were Naomi’s cue. She fixed Reyna with a dark look: the appropriate hate-filled face that she knew Reyna wouldn’t take seriously. It had to be done, though. Her face had to be maintained. And it wasn’t hard to dredge up the look. She had had enough practice and Reyna was sufficiently annoying.

‘The further ahead you look, the less definite the consequences. By making your moves based on a distant future you are gambling with our status instead of theirs,’ Naomi argued.

‘Have you considered the couple fully, though? They have very favourable chances for success, especially with our influence. And of course, by “our” I mean Schuyler’s influence.’

Schuyler sighed and said:

‘I wish you would call me Dad.’

Naomi snorted.

‘Please. “Dad” sounds so low level,’ Reyna told him. ‘It’s practically menial.’

‘“Father” then. Or “Pater”,’ he laughed. ‘Just stop using my name as if I were merely an acquaintance.’

‘You are merely an acquaintance,’ Reyna said.

‘This is what I get after having raised you all your life. I hope you never choose to have children,’ he said.

Naomi looked at Reyna, curious about her response. Reyna shrugged.

‘Well, that will depend on whether or not it’s beneficial to my status in the future. You know that. I do think there are unjustifiable risks involved in choosing children, however. Fashions are changing so quickly that I think human life is just too long to bother investing in it. You choose your child and by the time it’s born and finally grows into the looks and mind you chose for it, it’s already out of date. You have to be mind readers to get it right. And even then, there’s no predicting the public’s appetites. If there was a way to have interchangeable children, all at the different stages of life, then there would be some merit in the whole enterprise. We could change them the same way we change our faces—choose the most appropriate one for the day we’re going to have.’

‘For once, I agree with my sister,’ Naomi said.

‘Such smart girls,’ Madeleine said, and she raised her glass to Schuyler. ‘We chose such smart girls.’

The disgusted look Schuyler gave Madeleine was surprising. Virulent and uncharacteristic; Naomi found it necessary to take a deep breath and count to eight in response. It helped her keep up the appearance of being unmoved. She looked at Madeleine and wasn’t surprised to see her face crumbling. Madeleine stood up.

‘I have to use the amenities,’ she said. Wise choice. They watched her walk away.

‘Father?’ Reyna said, once Madeleine was out of earshot.

‘Have you considered yourselves?’ Schuyler said so abruptly that for a moment Naomi was confused as to what he was talking about. ‘You’re here because I chose you,’ he continued. ‘You speak so cavalierly about interchangeable children and the pros and cons of choosing lives. What of yourselves? What would have become of you if I had thought about children the way you are now?’

Naomi looked at Reyna.

‘I doubt I would have been born,’ Reyna told him. She spoke steadily, her face carefully presenting cool reason and lack of emotion.

‘How does that make you feel?’ Schuyler asked her.

‘That’s a redundant question. I am and so I can’t possibly say how I might feel about having not been.’

‘That’s weak, Reyna. You know that’s not what I was asking. What about you, Naomi?’ Schuyler asked.

Naomi shrugged and affected a bored drawl as she said:

‘This conversation is too full of hypotheticals for my taste. I would rather be on the In right now.’

‘We haven’t finished dinner,’ Schuyler said.

‘I have no appetite.’ Naomi stood up and slipped up the stairs before Schuyler could argue with her.

The true answer to his question was that Naomi wished he had thought about children the way she did. A second child was an unnecessary affectation. Naomi, when she realised this, was surprised Schuyler had allowed for her to happen. She was disappointed in him. If she had been given the choice she would have preferred not to have been born. And not just because she was an unnecessary second child. Life just seemed so pointless. And, on top of that, it was such hard work.

Naomi had the skills. She was quite good at faceplay and she knew she would do well in life. Not as well as Reyna, though; Reyna was the expert, a closed book. And it didn’t even matter that sometimes she used beta blockers; the point was that she had no personality. This made her almost perfect. Naomi, on the other hand, was afflicted with personality—but she had learned how to use it.

Naomi played the ‘teenage cliché’ with absolute precision. She had chosen the face when she was nine and spun it into a popular attraction. She had garnered a surprising following for her simple recordings of pure insolence. She was admired. Where Reyna juggled faces with the dexterity of an eight-armed goddess, Naomi had learned that she could make less count for more. It didn’t mean she enjoyed it, though.

Naomi had been informed, at age seven, that she was going to start school. Physical school. Reyna had been enrolled for two years prior, and had flourished. It was time for Naomi to follow in her footsteps. Naomi was not happy. At seven, she hadn’t yet learned how to control herself. She cried. Then she begged. She begged through her tears and her snot and her sobs. Madeleine threw a box of tissues at her and told her to grow up. Schuyler… Naomi couldn’t remember what Schuyler had done, only that he hadn’t helped her, and the very next day the household menial was taking her and Reyna to physical school.

Reyna—perfect Reyna—abandoned her at the gates and Naomi realized she would have to swim alone. This was her first proper lesson.

Naomi was reasonably clever. It didn’t take her long to figure out the purpose of physical school: it was a crucible. The only way to come out of it was to master faceplay. And it didn’t take her long to get the hang of that.

Still. Her face was beginning to wear on her. She couldn’t drop it—it had too many fans—and she didn’t want to develop it either. The whole thing was just so boring.

When she got back to her room, Naomi picked up where she’d left off in Psychology: The Science of Mind and Behaviour, 98th edition, and she thought about her project. Menials. That might not be boring. That might actually be very interesting.

Excerpted from Face, copyright © 2022 by Joma West.